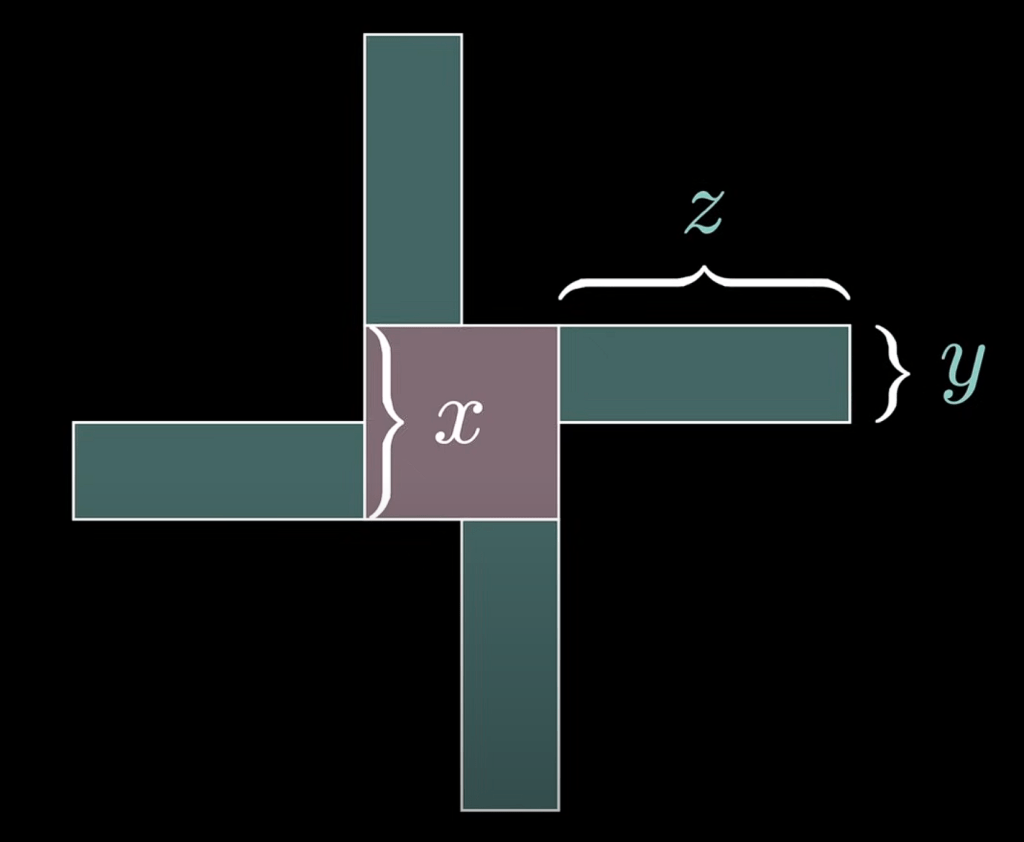

Featured image: Image of Pythagorean Windmills which satisfy W17: (1,1,4), (1,4,1), (1,2,2), (3,1,2), (3,2,1).

Hello everyone! My name is Alvin, and last year, I was granted the unique opportunity to choose and present a math proof for my Precalculus 11 class. This article is a showcase of Zagier’s famous one sentence proof. It initially piqued my interest, not simply for its brevity, but for its visual pairing of windmill structures.

Fermat’s Christmas theorem (or more officially recognized as Fermat’s Two Squares Theorem) proposes:

Every prime of the form p = 4k + 1 can be expressed as the sum of two squares (p = x2 + y2).

given x, y, and k are integers

This particular number is called a Pythagorean prime where the prime is congruent to 1 mod 4 (see Modular Arithmetic).

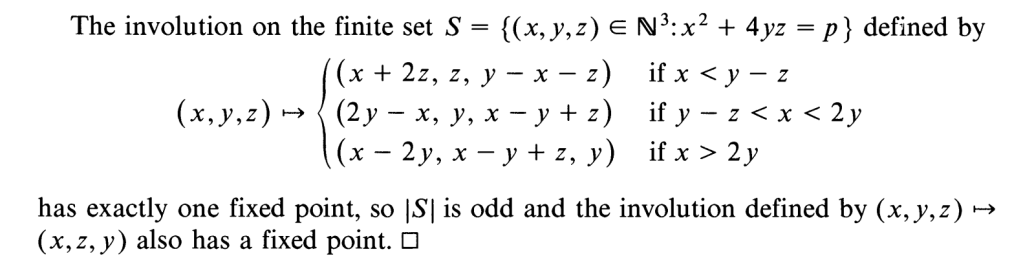

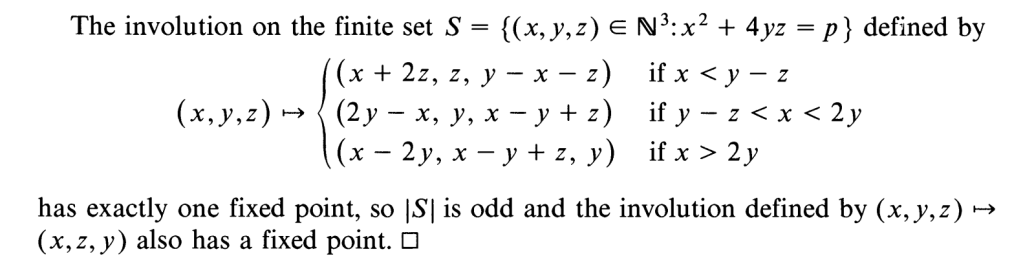

Over many centuries, many mathematicians have attempted to prove this theorem: the earliest proof (1752) was published by Euler using concepts of infinite descent; then came Lagrange, and his proof (in 1775) founded on the study of quadratic forms; Dedekind used gaussian integers, and Minkowski’s proof employed convex sets. In 1990, Zagier, simplifying Heath-Brown’s proof, presenting it in one sentence. Here is Zagier’s proof:

To interpret this proof, we must first understand the definition of an involution. An involution (also known as an involutory function or self-inverse function) is bijective for all x in its domain, and it must satisfy the condition where:

In other words, the function is its own inverse. One notable feature of an involution is that the parity of the size of the set of elements (in the involution f(x)) is solely dependent on the parity of the number of fixed elements (elements where f(x) = x):

Windmill Set

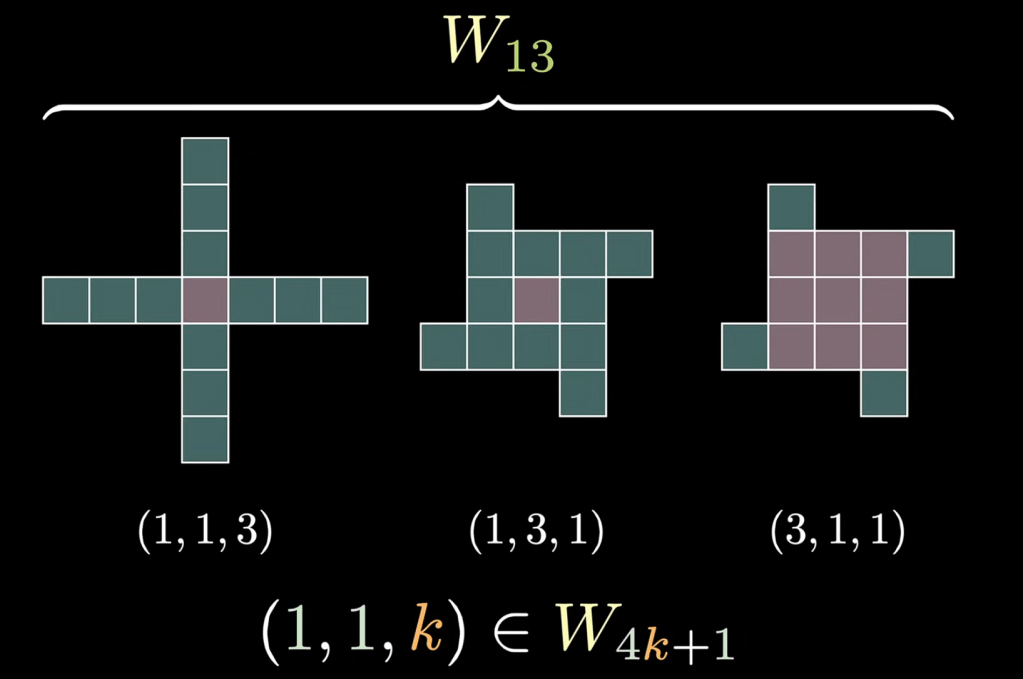

The form p = x2 + y2 is first substituted for p = x2 + yz; in doing so, we’ll need to further prove that y = z exists and satisfies the condition for each case. Though this may seem like an overcomplication, it allows us to establish this beautiful proof—using a windmill-like structure:

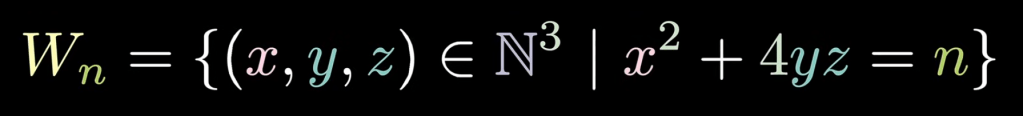

Consider the following set Wn which contains windmills representing Pythagorean primes:

When we consider the case where y = z, you can notice that Wp can indeed be broken down into a sum of squares:

p = x2 + 4yz → p = x2 + 4y2 → p = x2 + (2y)2

given y = z

Next, consider the example W13 where k = 3 (13 = 4k + 1):

When substituting the values (1,1,k) for (x,y,z) back into the original set Wn, we can notice that the equation always satisfies our original p = 4k + 1. Hence, we’ve established that this one windmill (1,1,k) always exists for Pythagorean primes.

However, we can further establish that (1,1,k) is the only windmill where x = y by using a contradiction of the very definition of prime numbers (decomposition of a prime). When x equals y, our original equation n = x2 + 4yz transforms into n = x2 + 4xz. By factoring x, we arrive at the equation n = x(x+4z). In this case, x cannot equal anything other than 1, since that would mean n contradicting the definition of a prime number. Therefore, we’ve also proven that (1,1,k) is the only windmill where x and y are equal:

n = x(x+4z), x = 1

x ≠ 1 leads to decomposition of a prime

Involutions

Consider the following involution on set Wn:

(x,y,z) → (x,z,y)

Recall our previous objective: if we are able to prove that (x,y,y) or y = z consistently exists as a windmill of set W4k+1, then we’ve proven that Pythagorean primes can be represented as a sum of two squares:

p = x2 + 4y2 → p = x2 + (2y)2

from p = x2 + 4yz

In our previous involution, y = z is a fixed point as the involution does not change the windmill:

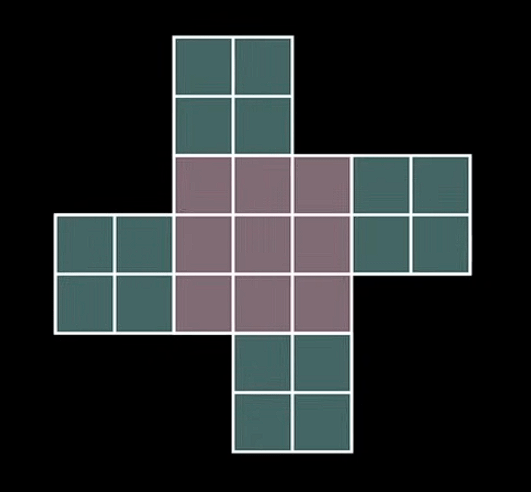

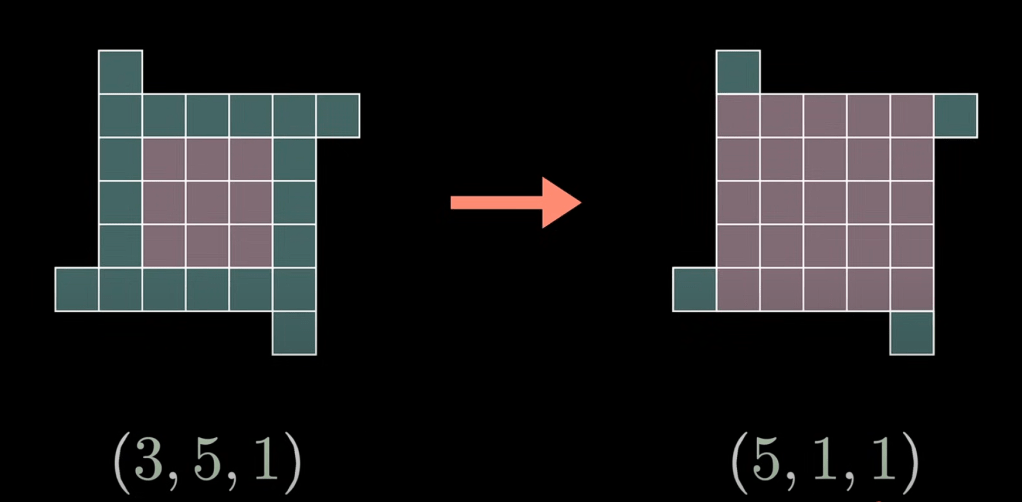

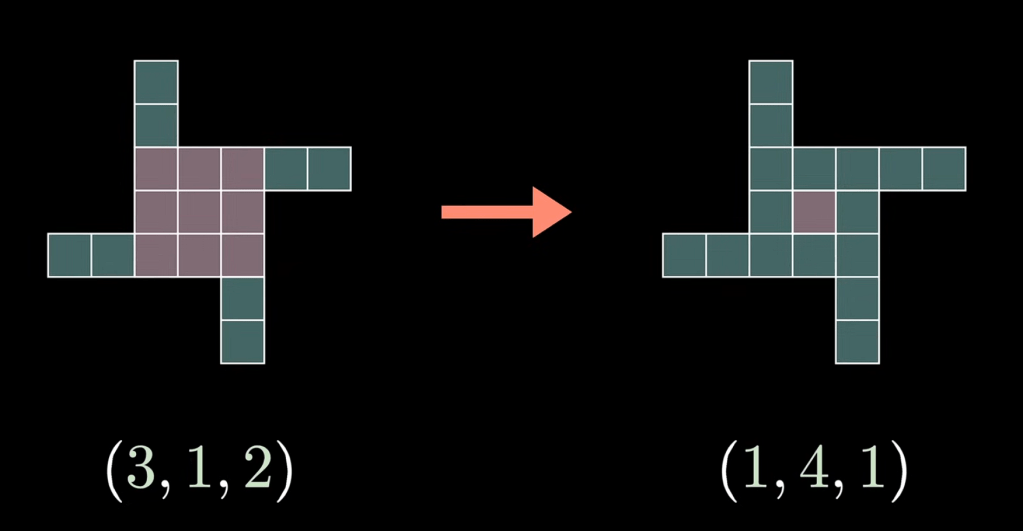

Now let’s consider another involution function, which can be more simply described visually. Consider the example W29:

The windmill is transformed by increasing x to expand to a larger central square. Though x and y have been changed, the total area is the same; henceforth, both windmills still satisfy the equation and belong in the set Wn. This process can also be reversed, where the arms and extended, thereby shrinking the central square:

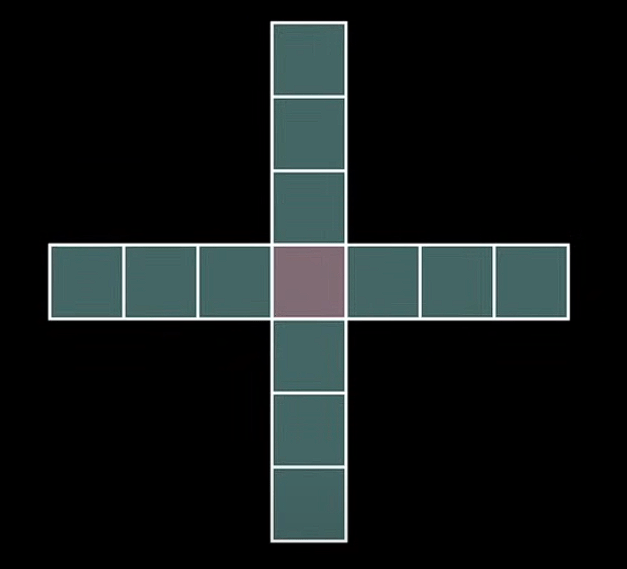

These two functions are in fact inverses of one another, making it an involutory function. Due to thorough casework, the involution is mathematically defined fairly complicatedly:

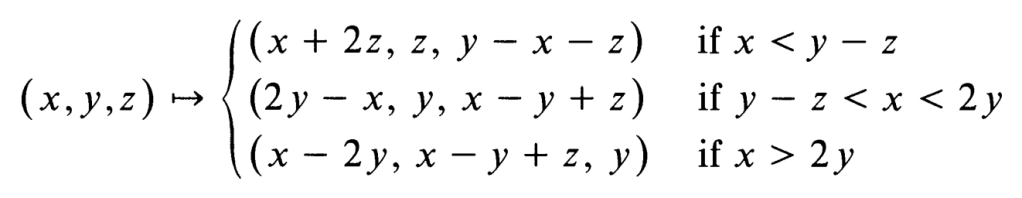

Notably, this involution also has a fixed point, which happens to occur when x is equal to y. The fixed point can be seen clearly visually as no extension of the square or arms is possible:

If you recall, we’ve already shown that (1,1,k) is the only possible case where x can equal to y. Thus, we’ve shown that one and only one fixed point will always exist for this involution on the set Wp.

Parity

The parity of the size of the set of an involution function is always determined by the number of fixed points or elements. With the second involution, we’ve established that the parity of the size of Wp is odd as there’s always one fixed point.

We’ve also determined that y = z in the involution (x,y,z) → (x,z,y) is a fixed point. Since the parity of the size Wp is always odd, we know that there’ll always exist at least one fixed point for the involution (x,y,z) → (x,z,y) and therefore a solution when y = z.

Zagier’s Solution

Zagier’s one-sentence proof is a highly condensed version of what has been unpacked here. If this proof is still confusing, I’d highly recommend accessing the following resource: visual proof

References

vcubingx. (2023). Is this the most beautiful proof? (Fermat’s Two Squares). In http://www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r2o11yHAa2U

Wikipedia Contributors. (2020, December 29). Involution (mathematics). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Involution_(mathematics)

Wikipedia Contributors. (2022, November 8). Fermat’s theorem on sums of two squares. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fermat%27s_theorem_on_sums_of_two_squares

Wikipedia Contributors. (2023, October 22). Pythagorean prime. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pythagorean_prime

Zagier, D. (1990). A One-Sentence Proof That Every Prime p≡1(\mod 4) Is a Sum of Two Squares. The American Mathematical Monthly, 97(2), 144. https://doi.org/10.2307/2323918